Diffusing Digits

Diffusing Digits - Generating MNIST Digits from noise with HuggingFace Diffusers

Diffusion models have become the state of the art generative model by learning how to progressively remove “noise” from a randomly generated noise field until the sample matches the training data distribution. Diffusion models are a fundamental part of several noteworthy text to image models, including Imagen, DALLE-2, and Stable Diffusion. However, they are capabilities beyond text to image generation and are applicable to a large variety of generative tasks.

Here a minimal diffusion model is trained on the iconic MNIST Digits database using several HuggingFace libraries. The flow follows that of the example HuggingFace notebook for unconditional image generation. I chose HuggingFace libraries for the implementation to learn their framework and I found that they were a nice balance between coding everything up in raw PyTorch (as was done in HuggingFace annotated diffusion blog post) and tailored implementations such as Phil Wang’s denoising-diffusion-pytorch.

Diffusion Models - Quick Explanation

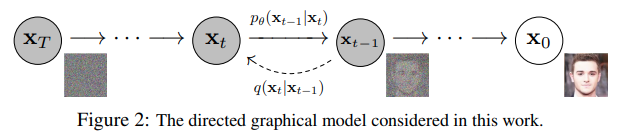

Conceptually, diffusion models are built upon a series of noising and denoising steps. In the noising process, random Gaussian noise is iteratively added to data (typically an image but can be any numeric datatype). After many steps of adding noise, the original data becomes indistinguishable from Gaussian noise. This noising process is going from right to left in the below figure from the Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models paper (often referred to as DDPM). In practice, getting from the original data to the step

The real juice of diffusion models is the denoising process. In the figure above, each denoising step (left to right in above figure), attempts to remove the noise added from previous step. Given noisy data, the diffusion model tries to predict the noise present in the data (slightly different to the above depiction which shows the model learning the conditional probability distribution

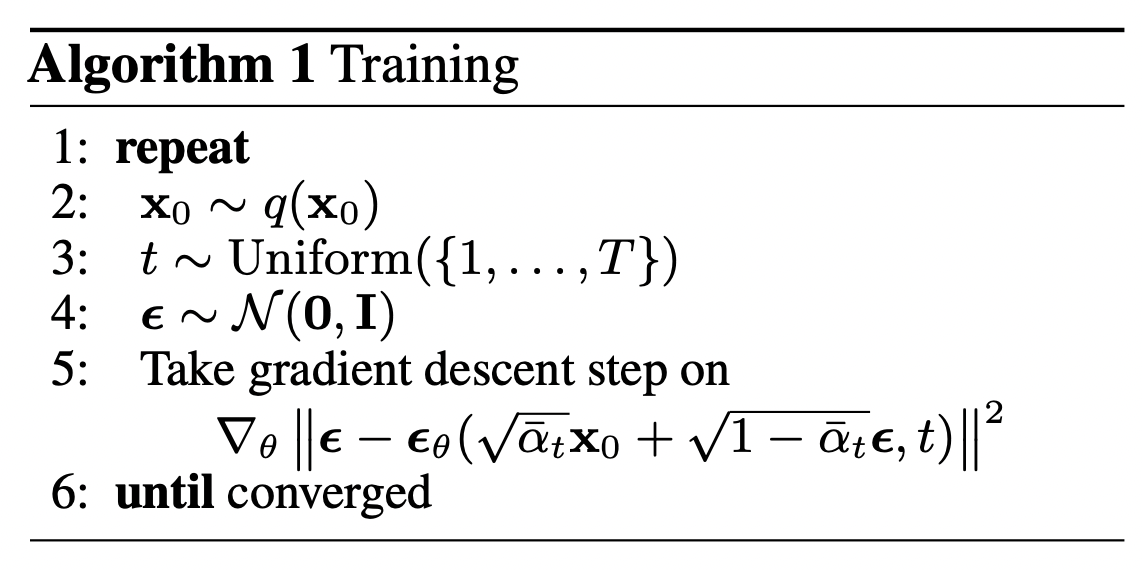

Diffusion models can be broken down into two algorithms, one for training and one for sampling.

Diffusion Models - Training

The training algorithm is relatively simple and follow the steps

- Take data from training distribution

- Randomly select a step within the noisig/denoising process

- Sample random Gaussian noise with zero mean and unit variance

- Take noise field and data from training distribution and noise it to selected step from noising process.

- Predict the noise present in the noisy data

- Update model based upon mean squared error of actual noise and predicted noise

Which is shown in the psuedocode from the Ho et. al paper.

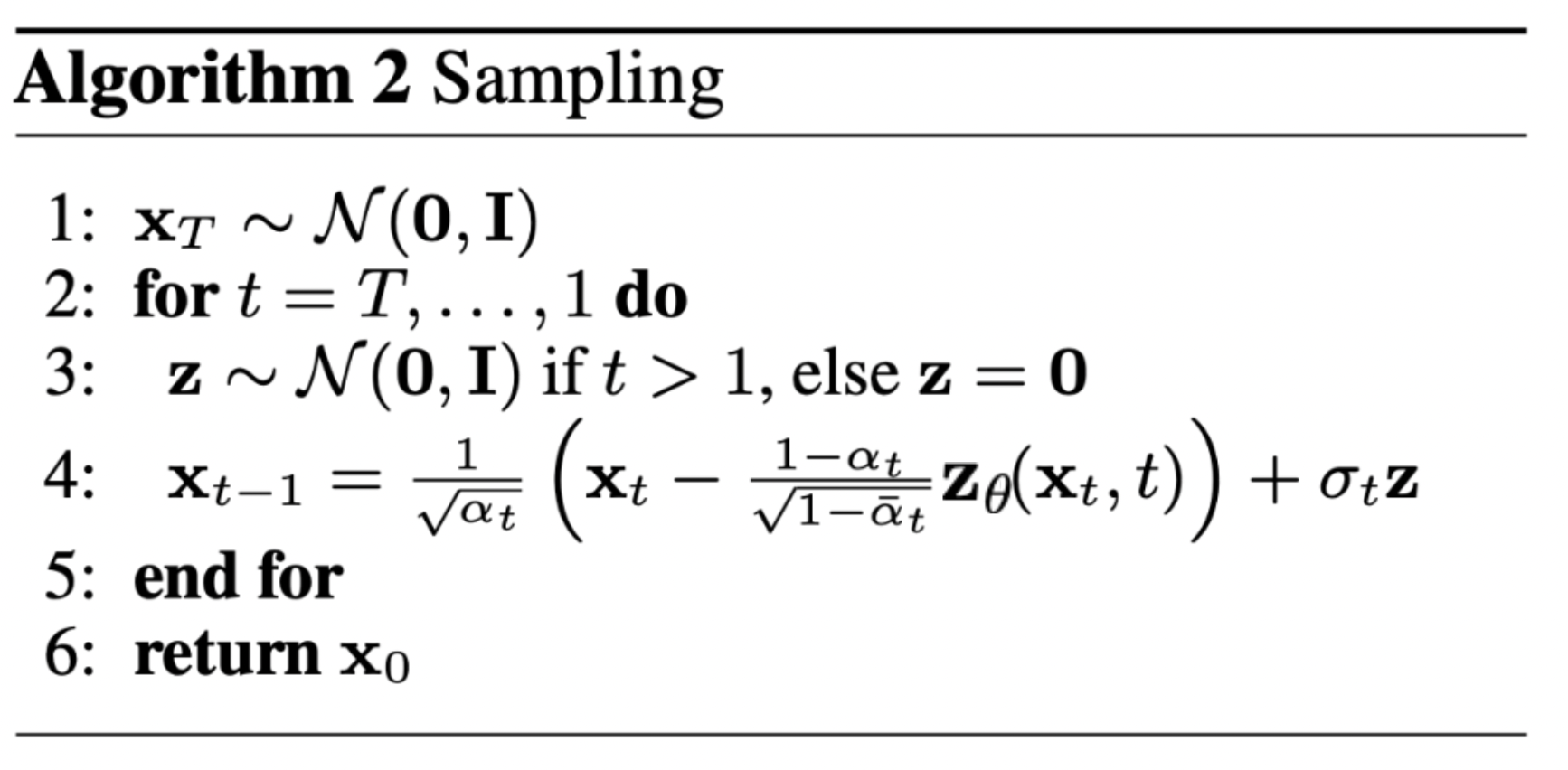

Diffusion Models - Sampling

With a model that takes a noisy image and predicts the noise given the step in the noising chain, can iteratively denoise the data with the following steps

- Generate the fully noised data at last step

- For each step in the chain, predict the noise in the image and remove some fraction of it.

Which is shown in the pseudocode

There are details about noise and learning rate schedules which were omitted from the above, but covered in the annotated diffusion blog post

Outline

In creating a diffusion model with HuggingFace, I found there to be 4 main stages after choosing the hyperparameters, each with defined subtasks. I’ve shown an outline below

- Defining Hyperparameters

- Preparing Dataset

- Creating the Diffusion Model

- Training the Model

- Sampling Images

Import libraries

# Pytorch

import torch

import torchvision

# HuggingFace

import datasets

import diffusers

import accelerate

# Training and Visualization

from tqdm.auto import tqdm

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import os

import PIL

Defining Hyperparameters

In the training config class shown below, I’ve chosen an image size of

The batch sizes chosen are done in order to comfortably fit on a 8 GB memory GPU. I find that training occupies approximately 4 GB of memory. Since one epoch contains all sixty thousand training examples, only a couple epochs are needed for the model to converge, with most of the learning being done within the first epoch.

The lr_warmup_steps is the number of mini-batches where the learning rate is increased until hitting the base learning rate listed in learning_rate. After the learning rate reaches this value, a cosine scheduler is used to slowly decrease the learning rate, as described in Improved Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class TrainingConfig:

image_size=32 #Resize the digits to be a power of two

train_batch_size = 32

eval_batch_size = 32

num_epochs = 5

gradient_accumulation_steps = 1

learning_rate = 1e-4

lr_warmpup_steps = 500

mixed_precision = 'fp16'

seed = 0

config = TrainingConfig()

Preparing MNIST Dataset

Downloading MNIST with HuggingFace datasets

HuggingFace has almost ten thousand dataset for download, which can be searched from the datasets tab of their website. They can be downloaded with their datasets python library and the load_dataset() function.

If not specified, the data will be downloaded to the ~/.cache directory. If you want to put the files in another location, either specify the data_dir optional argument or change the environment variable HF_DATASETS_CACHE to the desired path.

Here MNIST digits are loaded into a Dataset object, where metadata, labels, and images can be accessed in a manner similar to python dictionaries.

mnist_dataset = datasets.load_dataset('mnist', split='train')

The dataset object is conveniently accessible with methods similar to a python dictionary

mnist_dataset

Dataset({

features: ['image', 'label'],

num_rows: 60000

})

mnist_dataset[0]["image"].resize((256, 256)).show()

print("Image Size:", mnist_dataset[0]["image"].size)

print("Digit is labelled:", mnist_dataset[0]['label'])

Image Size: (28, 28)

Digit is labelled: 5

Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

As downloaded, the MNIST dataset contains 60,000 PIL images with pixel values in the range of

Three transforms are used. The first transforms the image to 32x32, in order to for the image width/height to be a power of two. The second transform turns the PIL image to a PyTorch tensor. When converting to a PyTorch tensor, the pixel range is transformed from

The Datasets object has a method set_transform() which applies a function which takes the dataset object as an argument. Here the method is used to apply the torchvision transforms to the MNIST dataset.

def transform(dataset):

preprocess = torchvision.transforms.Compose(

[

torchvision.transforms.Resize(

(config.image_size, config.image_size)),

torchvision.transforms.ToTensor(),

torchvision.transforms.Lambda(lambda x: 2*(x-0.5)),

]

)

images = [preprocess(image) for image in dataset["image"]]

return {"images": images}

mnist_dataset.reset_format()

mnist_dataset.set_transform(transform)

Once the dataset has been prepared with the proper transformers, it is ready to be passed directly into a PyTorch DataLoader.

train_dataloader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(

mnist_dataset,

batch_size = config.train_batch_size,

shuffle = True,

)

Creating the Diffusion Model

U-Net for MNIST

The workhorse of the denoising diffusion model is a U-Net, which is predicts the noise present in the input image conditioned on the step in the noising process. HuggingFace’s Diffusers library has default a U-Net class which creates a PyTorch model based upon the input values. Here the input and output channels are set to one since the image is black and white. The rest of the parameters mirror the choices found in the example notebook from HuggingFace.

model = diffusers.UNet2DModel(

sample_size=config.image_size,

in_channels=1,

out_channels=1,

layers_per_block=2,

block_out_channels=(128,128,256,512),

down_block_types=(

"DownBlock2D",

"DownBlock2D",

"AttnDownBlock2D",

"DownBlock2D",

),

up_block_types=(

"UpBlock2D",

"AttnUpBlock2D",

"UpBlock2D",

"UpBlock2D",

),

)

Check that the input image to the model and the output have the same shape

sample_image = mnist_dataset[0]["images"].unsqueeze(0)

print("Input shape:", sample_image.shape)

Input shape: torch.Size([1, 1, 32, 32])

print('Output shape:', model(sample_image, timestep=0)["sample"].shape)

Output shape: torch.Size([1, 1, 32, 32])

Noise Scheduler

In diffusion models, the noise is added to images dependent on the step within noising/denoising process. In the original DDPM paper, the strength of the noise added to the image (i.e. the variance of the zero mean Gaussian) increased linearly with time steps. The Diffusers library has a noise scheduler object which handles the amount of noise to be added for a given step. The default values for noise are taken from the DDPM paper, but there are optional arguments to change the starting and ending noise strength, along with the how the noise changes with across steps.

noise_scheduler = diffusers.DDPMScheduler(num_train_timesteps=200, tensor_format='pt')

We can take a digit and use the scheduler object to add noise. Below is the

print("Original Digit")

torchvision.transforms.ToPILImage()(sample_image.squeeze(1)).resize((256,256))

Original Digit

noise = torch.randn(sample_image.shape)

timesteps = torch.LongTensor([199])

noisy_image = noise_scheduler.add_noise(sample_image,noise,timesteps)

print("Fully Noised Digit")

torchvision.transforms.ToPILImage()(noisy_image.squeeze(1)).resize((256,256))

Fully Noised Digit

Optimizer

Let’s have the U-Net can learn with the AdamW optimizer.

optimizer = torch.optim.AdamW(model.parameters(),lr=config.learning_rate)

Learning Rate Scheduler

As mentioned previously, in Improved Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models, they find a learning rate schedule which first warmups for a fixed number of steps and then follows a cosine schedule thereafter to be effective in training the model. The diffusers library has a method which creates a PyTorch learning rate scheduler which follows the advice given in this paper.

# Cosine learning rate scheduler

lr_scheduler = diffusers.optimization.get_cosine_schedule_with_warmup(

optimizer=optimizer,

num_warmup_steps=config.lr_warmpup_steps,

num_training_steps=(len(train_dataloader)*config.num_epochs),

)

Training the Model

Working with memory restrictions

Running this on my local machine, I found that unless I set a limit on the VRAM accessible to PyTorch it would use it all up. This is good for maximizing utilization of a GPU cluster, but bad when iterating on a machine where the same GPU is rendering the operating system.

To get around this, there is a useful cuda function within PyTorch which sets the maximum fraction of total memory accessible. I’ve set this to use 7 GB out of 8 GB, just so computer doesn’t come to a standstill.

torch.cuda.set_per_process_memory_fraction(7./8., 0)

Creating and Running Training Loop

The training function first creates a HuggingFace accelerator object. The purpose of the accelerator object is to automatically handle device assignment for PyTorch objects when training on multiple devices and to make the code portable when running in multiple setups. Once created, the accelerator has a method prepare which takes all of the model/U-Net, optimizer, dataloader, and learning rate scheduler and automatically detects the correct device(s) and makes the appropriate .to() assignments.

After those objects are “prepared”, the training has an outer for loop for each epoch and an inner for loop for each mini-batch. In each mini-batch, a set of digits is taken from the dataset. Random noise with the same size of the minibatch is then sampled. Then, for each image in the minibatch, a random step in the noising process is (uniformly) selected. Noise is then added to each image based upon the randomly sampled noise and the randomly selected step. The U-Net then predicts the noise added to the image conditioned on the selected step. A mean squared error loss is then calculated between the predicted noise and the actual noise added to the image. This loss is then used to update the weights for each mini-batch.

def train_loop(

config,

model,

noise_scheduler,

optimizer,

train_dataloader,

lr_scheduler):

accelerator = accelerate.Accelerator(

mixed_precision=config.mixed_precision,

gradient_accumulation_steps=config.gradient_accumulation_steps,

)

model, optimizer, train_dataloader, lr_scheduler = accelerator.prepare(

model, optimizer, train_dataloader, lr_scheduler

)

for epoch in range(config.num_epochs):

progress_bar = tqdm(total=len(train_dataloader),

disable=not accelerator.is_local_main_process)

progress_bar.set_description(f"Epoch {epoch}")

for step, batch in enumerate(train_dataloader):

clean_images = batch['images']

noise = torch.randn(clean_images.shape).to(clean_images.device)

batch_size = clean_images.shape[0]

# Sample a set of random time steps for each image in mini-batch

timesteps = torch.randint(

0, noise_scheduler.num_train_timesteps, (batch_size,), device=clean_images.device)

noisy_images=noise_scheduler.add_noise(clean_images, noise, timesteps)

with accelerator.accumulate(model):

noise_pred = model(noisy_images,timesteps)["sample"]

loss = torch.nn.functional.mse_loss(noise_pred,noise)

accelerator.backward(loss)

accelerator.clip_grad_norm_(model.parameters(),1.0)

optimizer.step()

lr_scheduler.step()

optimizer.zero_grad()

progress_bar.update(1)

logs = {

"loss" : loss.detach().item(),

"lr" : lr_scheduler.get_last_lr()[0],

}

progress_bar.set_postfix(**logs)

accelerator.unwrap_model(model)

Once the training loop set up, the function along with its arguments can be passed to the accelerate library’s notebook launcher to train within the notebook.

args = (config, model, noise_scheduler, optimizer, train_dataloader, lr_scheduler)

accelerate.notebook_launcher(train_loop, args, num_processes=1)

Create a sampling function

Once the model has been trained, we can sample the model to create digits. Or more accurately create a sample which is within the learned distribution of the training samples, since some generated samples look like an alien’s numbering system, a mish-mash of the numbers 0-9.

To sample images, the Diffusers library has several pipelines. However, I found that these pipelines don’t work for single channel images (which is now fixed!). So I created a small function which samples the images, with an optional argument for saving off each step. Importantly, the function needs to have a torch.no_grad() decorator so the model doesn’t accumulate the history of the forward passes.

@torch.no_grad()

def sample(unet, scheduler,seed,save_process_dir=None):

torch.manual_seed(seed)

if save_process_dir:

if not os.path.exists(save_process_dir):

os.mkdir(save_process_dir)

scheduler.set_timesteps(1000)

image=torch.randn((1,1,32,32)).to(model.device)

num_steps=max(noise_scheduler.timesteps).numpy()

for t in noise_scheduler.timesteps:

model_output=unet(image,t)['sample']

image=scheduler.step(model_output,int(t),image,generator=None)['prev_sample']

if save_process_dir:

save_image=torchvision.transforms.ToPILImage()(image.squeeze(0))

save_image.resize((256,256)).save(

os.path.join(save_process_dir,"seed-"+str(seed)+"_"+f"{num_steps-t.numpy():03d}"+".png"),format="png")

return torchvision.transforms.ToPILImage()(image.squeeze(0))

Sample some good looking digits!

Some samples look quit good…

test_image=sample(model,noise_scheduler,2)

test_image.resize((265,256))

test_image=sample(model,noise_scheduler,5)

test_image.resize((256,256))

test_image=sample(model,noise_scheduler,1991)

test_image.resize((256,256))

But others aren’t quite recognizable as a number, but look like they could be number if history went slightly differently…

test_image=sample(model,noise_scheduler,2022)

test_image.resize((256,256))

test_image=sample(model,noise_scheduler,42)

test_image.resize((256,256))